Halfway There, Livin’ on a Stair: The History of the Split Level Home

Introduction

At the dawn of the twentieth century house forms began to radically shift as the number of middle-class Americans exploded, cultural mores relaxed, and notions about housing design and functionality began to change just as dramatically as cultural traditions. Several utterly unique residential house forms were developed in the early decades of the twentieth century including the ranch home and the split-level home. The advent of the ranch has been relatively well explored by architectural historians but the split-level house, as a unique piece of domestic architectural design, has been somewhat neglected by formal histories on residential architecture. While always mentioned in treatises, a thorough history of the split-level home deserves a closer look. In this blog post I will explore the history and design antecedents of the split-level home, the various forms the houses take, and I will attempt to provide reasoning for the sudden proliferation of this house type in the mid-twentieth century. I also attempt to explain where the split-level home came from and why split-level homes were so appealing to mid-century builders and buyers.

There have been some very good investigations into the split level and a few architectural historians have presented on this topic (most notably Dr. Richard Cloues from the Georgia Department of Natural Resources—Historic Preservation Division) and this blog post builds off of that work. Dr. Cloues’s work was extremely important as it seems to be the most exhaustive look into the evolution of the split level but if you know of any other good sources, let me know!

Methodology

Where else did I look? Scholarly literature, archives, libraries, and historic floorplan books were consulted to build a history of the split-level house. Historic floorplan and pattern books were especially useful as it presented the easiest way to quickly search for design precedents that might hint toward the origins of the split level: sunken garages with ancillary living spaces above, maid’s quarters above kitchens, and early finished “recreation rooms” in hillside basements—all found at a slightly different grade than the primary living areas—may have been an impetus to separate noncompatible living areas by shorter staircases.

After tracing the general history and origins of the split level, three houses (all located in Michigan because that’s where I live) are used as illustrative examples as they stand as waypoints in the history of the split level: a very early example of a Sears kit house split-level built in 1939 at 1815 Edgewood Drive, Berkley MI (see Figure 1); a mid-century example built in 1957 located at 19251 Bretton Drive, Detroit MI (see Figure 2); and a later example built in 1963 located at 23284 Plumbrooke Drive, Southfield MI (see Figure 3).

Figure 1: An early split level is the 1939 Sears Kit house found at 1815 Edgewood Drive, Berkley, MI

Figure 2: A mid-century split level built in 1957 and located at 19251 Bretton Drive, Detroit MI

Figure 3: A later split level built in 1963 at 23284 Plumbrooke Drive, Southfield MI

Before we dive in, let’s talk a little nomenclature. It is important to note that a split-level house is a house form not a style. A split-level house (as a form) can be found in many architectural styles with ranch, stylized ranch and contemporary being the most common styles of the split-level form, according to Virginia McAlester’s landmark book Field Guide to American Houses.[1] We’re not talking style in this post, we’re focusing, primarily, on the form itself and the progression of that form, over time.

There is much discussion amongst architectural historians and preservationists as to what a “split level” actually is. Dr. Cloues defines it as a house with three levels: main ground floor living area accompanied by a two-story section with bedrooms half a flight (usually up) from the ground floor living area and a utility or garage or recreation room a half a flight (usually down) from the ground floor living area. McAlester also defines a split level as a house that has “three or more separate levels that are staggered and separated from each other by a partial flight of stairs rather than a full flight.”[2] But McAlester further differentiates split-levels into two sub-categories: a bi-level split and a tri-level split. Notably, McAlester’s terminology does not pick out a decided third type: the quad level. The quad level, of course, has four distinct levels of living space. For purposes of this paper, a split-level home is a home that contains at least two levels of living space separated by anything less than a full flight of stairs.

There seems to be some professional dispute as to whether a split-entry (with only the entry found at the half-way point) is a true split level but McAlester at least confirms that it is. For this paper, the split-entry will not be discussed as it does not contain living space separated by less than a full flight of stairs. The entry in most split-entry homes is the only portion (generally a very small portion) of the home found at the termination point of the “less than a full flight of stairs” and thus does not really qualify as a living space.

A discussion amongst members of the Facebook group “Historic Preservation Professionals” illustrates both the wide range of terms used and the confusion over the true definition of a split level as all of the following terms were used in a discussion on this exact topic in November and December of 2020: tri-level, bi-level, split-level, side-splits, dipsy-doodle, quad-level split, raised ranch, split-entry, three level split, California split, and off-set split. These are professional architectural historians and historic preservationists, and, surely, the sheer number of terms contributes to some of the complexities of this topic. Ultimately, it seems that various preservation professionals use slightly different terminology to discuss these types of homes with many professionals adding additional qualifiers to further delineated various forms. This paper uses a blend of McAlester’s terminology (bi-level split, tri-level split) but adds quad-level split to further distinguish the most prevalent sub-types.

Although there are examples of bi-level splits (two levels of living space) and quad-level splits, at least one source states that the tri-level split is the most common iteration of the sub-types. at least one source states that the tri-level split is the most common iteration of the sub-types.[3] And this makes sense: imagine a bi-level split with two areas of living space separated by a less-than-full-height staircase, and it is easy to see that there is room for a third level of living space should the designer take advantage of it. The reality is that some builders only provided two levels of living space, but the vast majority added the third level of living space below the upper portion that was set off from the main living area with a partial staircase.

History

Pinpointing the advent of the split-level home has been the subject of some conjecture, and it very well may be impossible to definitively find the “first” example of this unique form but Richard Cloues posits that Frank Lloyd Wright’s Storer House built in 1923 might be the first “fully developed split level.” Given Wright’s massive prominence and popularity, the Storer House may have been the impetus behind the proliferation of the split level across the United States.[4] It may be impossible to fully vet this claim, but it does seem like a plausible theory.

Certainly, there are early examples of the split level occurring in California built (in the 1920s and 1930s) out of necessity in order to maximize living space in homes that were built on small, steeply sloped lots. Dr. Clouse’s work in this area is instructive as he identified several of these very early prototypes in California. These homes were not marketed as “split level” but were a design necessity as a result of the topography surrounding the population centers of California, namely, San Francisco and Los Angeles. Figure 4 provides an example, the first “Doelger” house—so named because of the builder Henry Doelger—which was constructed in 1925.[5] The tri-level form is immediately discernable from the exterior façade given the attached garage and raised entry.

Figure 4: The first Doelger-built home in San Francisco, circa 1925

Even earlier split-level antecedents might be found in unusual places if we examine the idea of placing different domestic functions at varying floor levels—and there are many examples of this that pre-date the introduction of the true split level in the 1920s and 1930s. The notion that certain living spaces should be set apart from other, non-compatible living areas finds its origins perhaps in the early 1900s when architects and builders often placed servants’ quarters over a kitchen, which was, in turn, often several feet shorter than the core block of the building. This resulted in maids’ rooms, chauffeurs’ rooms and, sometimes, the nursery—with its necessary accoutrement the hired nanny—being placed at a different level than the principal occupants of the house. Much like modern split levels, this arrangement provided both privacy and a clear delineation of the relative importance of the home’s occupants. A maid is, of course, lower than the owner and thus her room is several steps lower (literally) than the owner’s bedroom.

In 1909 Gustav Stickley published Craftsman Homes, and this book contains many examples of the homes he designed. In looking through these plans it’s interesting to note the plan found on page 11 (see Figure 5). The servant’s bedrooms—although not labeled as such, the size and location at the back of the house, over the kitchen indicates they were assuredly bedrooms for domestic staff—are located a half level down from the main floor bedrooms.

Figure 5: 1909 design by Gustav Stickley

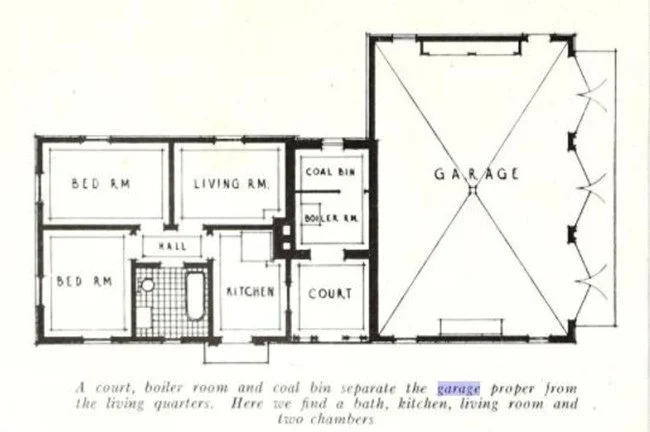

Garages also prove to be instructive when searching for early split-level antecedents. Some of the earliest garages were standalone buildings found on large estates that generally included functions associated with automobiles: chauffeurs’ quarters, mechanical functions, and, sometimes, recreational spaces (see Figure 6). This grouping of service functions—clearly ancillary activities not warranting inclusion in the house—above and surrounding the garage space itself is instructive as this general “use grouping” is repeated in later designs when the garage is fully attached to the house.

Figure 6: Detached Garage with service spaces and chauffeurs house, 1919

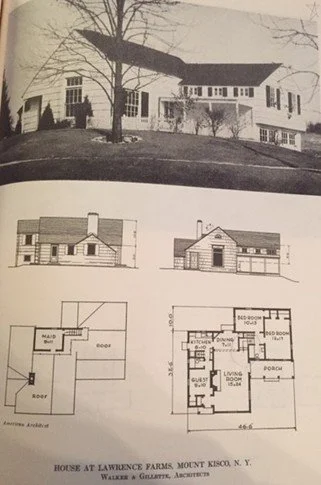

Once garages become attached to the house itself, this division of space is repeated. Almost universally in these early attached garage examples, the spaces above an attached garage are devoted to servants’ quarters, storage, bathrooms, or closets. And, because garages are often located off the side of the house, at a lower grade, the spaces placed above the garage are several steps lower than the rest of the second floor—see Figure 7.

Figure 7: The attached garage with maid’s quarters above is placed four steps below the second-floor level of the core block, 1919

The novelty of an attached garage created some unique design options by early architects who clearly grappled with how to integrate this new space into a residential design. Various options were tried when trying to integrate the garage with the home. Early garage owners might build a whole separate building or, they “might encase them in what amounted to a fireproof box, built to comply with the city fire codes and inserted at or below ground level in the house…Owners of small, steep urban lots often inserted a garage into a bank at roadside…”[6] It perhaps makes sense then that some of the very first antecedents of the split levels are of this variety: the garage is inserted below grade, and because of lot confinements and the price of land, living spaces are added on top of the garage to maximize space. An early example of the attached garage with living space above (albeit outdoor living space in the form of a terrace) can be seen in Figure 8.

Figure 8: 1915 Bungalow (Radford) with sunken garage and a terrace above it

In 1934 the Architectural Book Publishing Company published American Country Houses of Today and it contained 108 total floor plans. Of these 108 plans 34 of them, or nearly a third, contain living spaces set apart by staircases—sometimes as few as one or two steps (a “sunken” room or wing of rooms) but often set off by four or five steps. As scholar Barbara Miller Lane points out, “Expensive houses had long been built on more than one level in hilly areas, especially in California” but it’s worth noting that the early split-level antecedent houses in American Country Houses of Today are found in not-so-hilly areas like Rumson, NJ and Long Island, NY.[9] This book features high end homes with nearly every plan providing maid’s quarters so perhaps it’s not surprising that so many plans have these subservient spaces set apart (and down a few steps) from the main living spaces. But there plans in this book that edge very close to true split levels (see Figure 9). This house features a full floor of living space (the maid’s room) set above the kitchen by what looks to be a partial height staircase.

Figure 9: An early split-level from American Country Houses of Today, 1934

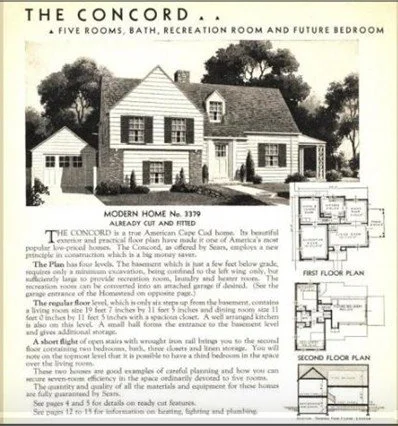

In 1933 Sears introduced the “Concord” which is a fully realized split-level home (see Figure 10). The Concord features an attached garage with owner-occupied (non-servant spaces, that is) living spaces overhead, accessed by a half staircase. The Concord was introduced in 1933 and continued to appear in Sears catalogues until 1940.[8]

Figure 10: The Sear’s Concord initially debuted in 1933

Of course, many of the split-level antecedents discussed here are not examples of true split-level homes. But the willingness, in the first two decades of the twentieth century, to divide living spaces onto different floor levels separated by a few steps or a half-stair, perhaps provided the inspiration to fully commit to this rearrangement of space. It seems likely that the split-level antecedents discussed above provided the first initial forays into “split level” design, but it was the marketing genius of the Sears Modern Homes program that really spread the split-level design across the country, launching the split-level into the mainstream design vocabulary.

The origins of the term “split-level” are not fully understood but Dr. Cloues found an early example in 1945 in a plan book (the earliest example he has found).[9] Another early use was found in 1947 in a LIFE magazine article about the Walker Art Center’s “Idea House” located in Minneapolis.[10] But it’s important to note that various designers and builders used different terms. Another advertisement from 1947 from the Ideal Plan Service called their split-level design a “Hi-Lo” house and Sears termed their early split-level designs “Stepped Up” houses. As discussed above, this varying nomenclature is hardly standardized even today.

By the 1940s the split-level was prevalent, but it wasn’t until the 1950s that the pinnacle of the split-level form—the quad-level—is seen with any regularity. The quad-level is virtually unseen in the first examples from the 1920s-1940s—I haven’t found an example in the 1930s or 1940s, but they could exist in limited numbers. The quad-level, as an expanded interpretation of the initial split-level design could be considered the zenith of the split-level design, which makes its nationwide debut in the 1950s once the general form had come into its own. What had started out as two separate levels of living (in the earliest examples found in the 1920s) reached its most fully developed form in the mid-century with four levels of living space. Split-level homes remained popular through the 1970s especially with the airing of the Brady Bunch—in which their split-level home featured prominently—and ebbed by the early 1980s. Very few split-level homes are built today as a search conducted on a modern home plans website, www.thehousedesigners.com, reveals 778 plans tagged under the category “ranch” and 444 plans tagged under the category “colonial” while “split-level” search retrieves only 82 plans, some of which are not split-level at all and appear to be tagged in error.[11]

Examples of Form

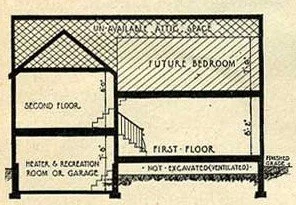

The split-level takes three basic forms: a home with two levels of living space (there is generally a third level, but it does not contain living space, instead housing a garage or a utility room), a home with three levels of living space, and a home with four levels of living space—all separated by less-than-full-height staircases. The earliest iterations tend to contain two or “two-quasi-three” levels of living space. The Concord, offered by Sears and discussed above, is a good example of this. The house contains two main levels of living space, separated by half-stair while the “quasi” third level contains a basement which the buyer could use as either a recreation room or as a garage. It is interesting to note that, even in 1933 when this home debuted, a fourth level was contemplated: should the family grow large enough and require additional space, there was an attic space above the main living level that could be converted to another bedroom (see Figure 11).

Figure 11: The Sears Concord shown in Figure 5, zoomed in.

There is a Sears Concord located at 1815 Edgewood Drive in Berkley, Michigan (see Figure 1 and 12) which was built in 1939. Because split-level homes provided more living space with less excavation (which was a costly portion of the construction budget) these homes were attractive to post-Depression buyers and this likely spurred their popularity in the 1940s and beyond. As is evident from the advertisement (see Figure 12) this home was marketed as new and “different” and this must have appealed to homebuyers, many of whom would have grown up with no indoor plumbing—only 1% of U.S. homes had electricity and plumbing in 1920—so the epitaph “different” likely conjured positive feelings in the homebuying public of 1939. [12]

Figure 12: Advertisement for 1815 Edgewood Drive, Berkley, MI

If the initial forays into split-level design were begun as a means of saving on excavation costs and delivering more square footage per dollar spent, most quad-level designs completely disregarded this early cost saving principle. Quad-levels are, almost invariably, very large houses spread out over a huge footprint and the house at 19251 Bretton in Detroit is a prime example (see Figure 2). Necessitating both a partially sunken third level and a fully sunken fourth level, these homes—much like the suburban lots they are most often found on—just sprawl across the landscape. Given that the post-World War II economy was expanding rapidly during the 1950s when the quad-level proliferated, it seems likely the constricted budgets that may have influenced early split-level design were no longer a factor when houses like 19251 Bretton were built.

Built in 1957, the house at 19251 Bretton has a massive footprint containing over 3,900 square feet of living space. The lot is 167’ wide by 101’ deep and the home stretches approximately 112’ long from end-to-end (see Figure 13). This home features a main entrance that opens into a living room, dining room, study, kitchen and bathroom on the ground level, three bedrooms on the upper level, a recreation room, bathroom and additional room on the lower level, and a fully finished basement with another recreation room, laundry room, and many storage areas in the lowest level. Because the basement, the lowest level, is fully finished this home is a true quad-level, providing living spaces across four floors, all separated by half staircases.

Figure 13: Aerial photograph (from Google) of 19251 Bretton showing the width of the house

Figure 14: The lower-level recreation room in 19251 Bretton is shown here. The stair up to the main living level is visible in the background

After examining the first, early split-level designs it becomes clear that by 1957 when 19251 Bretton was built, the notion of providing different levels for different living areas was fully developed. But while there are four full floors of living space in this house, the lowest level was clearly a space used primarily for storage by the current owners. In fact, when walking through the house it almost feels as if the lowest level—while fully finished and ready for continual occupation—left the architect fumbling a bit: the level beneath the bedrooms already had a recreation room fitted with wet bar, kitchenette, and fireplace (see Figure 14) so the lowest level’s recreation room ends up functioning more like a glorified hallway (see Figure 15). Perhaps this is understandable, given the massive size and the full array of rooms found in the rest of the house—architects in 1957 weren’t yet designing home theater rooms and gyms in private homes so this space lacks the kind of luxury rooms found in most modern houses of this size.

Figure 15: Lowest level of 19251 Bretton

Figure 16: Entryway of 23284 Plumbrooke Drive

The final house form is a true tri-level split with three total floors of living space. The house at 23284 Plumbrooke Drive, Southfield, MI was built in 1963 and was designed by George Dunn Fonville.[13] Located in the Plumbrooke Estates subdivision, the whole neighborhood is comprised of various mid-century houses. The house at 23284 Plumbrooke was called the “Riviera” and it was advertised as a home with “pizazz.”[14] Much like the advertisement for the Sears Concord in Berkley, the marketers for the Riviera seems to be playing up the uniqueness of the split-level design. The house features a main entry that opens into a large foyer (see Figure 16), a kitchen with dining nook, dining room, and living room. There is a half-staircase that leads up to four bedrooms and two bathrooms, with the recreation room and additional bedroom are found below the bedrooms. The tri-level split is the most ubiquitous type of split-level as the main floor entry with two half-staircases (bedrooms up, family room down) lend themselves well to three total floors.

Figure 17: Lower-level family room in 23284 Plumbrooke Drive

Conclusion

While the ranch home may have been the most popular house form in the mid-century, Richard Cloues points out that the split level was a close runner up.[15] This popularity seems relatively easy to explain given that split level homes “combined some of the best features of the new Ranch House (which was wildly popular at the time) and the traditional two-story house (which was totally out of favor at the time) in an efficient, cost effective way.”[16] With three distinct sub-types the split-level seems imminently adaptable to many lifestyles and many budgets. There are numerous advantages to a split-level design: bedrooms are nearly always on a separate floor than the primary living area and both a formal living room and a more casual family room are both generally present.

Why this house form has been almost completely abandoned by modern homebuilders is likely a topic for another paper but it could stem from the immense popularity of “open concept” living spaces which exploded in popularity in the 1990s and whose origins likely trace back to mid-century antecedents when kitchens were often first opened up to a combined dining/living space.[17] With further research and documentation it may just be concluded that designers who created the split-level—radically altering the basic form of the American home—may have played a role in the ultimate demise of the very thing they created. But, because style is cyclical and, as designers continue to play with form and reimagine our interior living spaces, it seems like that the next iteration of the split-level is just a few steps (dare I say…a half-staircase?) away.

Bibliography:

Cloues, Richard. “National History of the Split-Level Home.” Georgia: Department of Natural Resources, Historic Preservation Division, March 2012.

Coffin, Lewis A. American Country Houses of Today. New York, NY: Architectural Book Publishing, Co., 1934.

Detroit Free Press

“Houses Have Pizazz, Too.” February 1, 1963

“5-Level Home Today.” July 16, 1939.

Goat, Leslie G. “Housing the Horseless Carriage: America’s Early Private Garages.” Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 3, (1989): 62-72.

Gottfried, Herbert, and Jan Jennings. American Vernacular Buildings and Interiors, 1870-1960. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009.

Lutz, James D. “Lest We Forget, a Short History of Housing in the United States.” Lawrence Berkley National Laboratory 2004, 1-190, accessed December 6, 2020 Lest We Forget, a Short History of Housing in the United States (aceee.org).

Miller Lane, Barbara. Houses for a New World: Builders and Buyers in American Suburbs, 1945-1965.

Mills, Ruth. “Plumbrooke Estates Historic District.” National Register of Historic Places Nomination, 2019.

Savage McAlester, Virginia. The Field Guide to American Houses. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013.

Stickley, Gustav. Craftsman Homes: Architecture and Furnishings of the American Arts and Crafts Movement. New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1979.

Sears home plans:

“The Concord”

“The Homestead”

“The Oldtown”

Wagner, Kate. “The Case For Rooms.” Bloomberg CityLab. August 6, 2018. Accessed December 6, 2020. Death to the Open Floor Plan. Long Live Separate Rooms. - Bloomberg