Is That A Pickle In Your Mitten Or Just A Field Of Cucumbers?

The answer to both of those questions is, unequivocally yes and yes. Because the Mitten State is partial to pickles and filled with fields of cucumbers, today we are going to dive into the dillightful history of Michigan’s poppin’ pickle production! Michigan’s temperate and humid climate, the railroad networks that crisscross the state, and vast swaths of well-draining, sandy soil—leftover after Michigan’s lumber boom turned its forests into agricultural fields—drove the development of agriculture in the state. One crop that put money into farmer’s pockets is the humble pickling cucumber.

Following the Civil War and on through the turn of the twentieth century, the burgeoning food processing industry in the United States steadily grew. Immense industrial and social change was brought about as the country’s population increased dramatically with European immigration and as people began to coalesce in urban areas. At the same time, women began transitioning from producers of household goods to consumers and entering the workforce, railroad networks connected agricultural areas to urban centers, and technological advancements, like the advent of Mason jars in 1858, took hold.

These changes helped foster the growth of companies with nationwide footprints that were capable of profiting from sourcing, processing, transporting, packaging, and advertising processed foods that were becoming increasingly sought after in the marketplace.[1] Many of these companies that developed in the late-nineteenth century are those we still recognize today like Quaker Oats, Campbell Soup, Pillsbury, and Heinz.[2] By the turn of the twentieth century, manufactured foods made up nearly one-third of the value of finished goods produced in the United States, and by 1920 nearly every household purchased some form of manufactured food.[3] Traditionally made by German, English, Polish, and Jewish women at home, pickles are just one example of a food that became mass produced at this time.[4] In the early decades of the twentieth century, Michigan had sizable German and Polish populations so it’s no wonder pickle production prospered here.

Like other industries at the time, Heinz relied on women workers, who were paid less than their male counterparts, who contributed to nearly all aspects of Heinz’s production.

H.J. Heinz Company, Photographs, 1864-1991, MSP 57, Library and Archives Division, Senator John Heinz History Center.

As it turns out, Michigan’s farmers and rural communities played a crucial role in the history of pickle production and in this article, we will see how Evart, Michigan and the H. J. Heinz Company contributed to this history. Heinz was by no means the only pickle producer in Michigan - other companies in Michigan’s small towns and cities contributed to this history as well. Hausbeck Pickles was founded in Saginaw in 1923 and distributed pickles to grocery stores throughout Michigan. World famous Vlasic was founded in Detroit and began selling pickles in the 1940s after opening a factory in Imlay City, Michigan. This illustrious lineage continues as McClure’s was founded in Detroit and Brooklyn in 2006 to manufacture and produce pickles based on an old family recipe.

Evart was founded in the spring of 1871 just before the Flint and Pere Marquette Railroad was laid across the Muskegon River on its way to Lake Michigan. The high-quality timber around Evart, the Muskegon River, and the railroad drew newcomers to the fledgling town and it quickly flourished. As the land was cleared of its timber through the remainder of the nineteenth century, Evart’s nearby forests gave way to rich farmland well suited for growing crops and grains.[5]

Just before Evart was founded, the H. J. Heinz Company was started by Henry Heinz in Sharpsburg, Pennsylvania in 1869. Over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Heinz was able to capitalize on and navigate the industrial and societal changes underfoot and grew his pickling and condiment company into a large corporation with a national presence. By 1910, Heinz had 12 branch factories in 8 states, a behemoth central factory in Pittsburgh, and 69 salting stations in 7 states.[6] Michigan had more salting stations and branch factories than any other state, with 45% of the company’s salting stations and 33% of the company’s branch factories, highlighting the integral part Michigan’s farmers and industry played in Heinz’s pickle production.[7] Heinz cultivated his business through a steadfast focus on quality ingredients, business and brand-building acumen, and vertical integration of the company’s supply chains, which turned fields of cucumbers into jars of Heinz pickles.[8]

A map of Heinz salting stations (black dots), branch factories (red dots), and distribution stations (red stars). Western, mid-Michigan had the most salting stations followed by northern Indiana and central Wisconsin.

H. J. Heinz Company, H. J. Heinz Company, Producers, Manufacturers and Distributors of Pure Food Products (Pittsburgh: H. J. Heinz Company, [1910]), HathiTrust.

The strategy Heinz used to obtain the quantity of quality cucumbers his factories required was to provide farmers with free cucumber seeds and cultivation instructions at the beginning of the growing season in exchange for the company’s purchase, at a set price, of ripe cucumbers at harvest. The company’s salesmen, known in local newspapers as the “Heinz Man,” or the “Heinz pickle agent,” traveled to communities throughout mid-Michigan in the spring and summer to secure cucumber contracts.[9]

An advertisement in the Osceola County Herald from April 15, 1920 urging all farmers to visit the Heinz man and plant cucumbers following Heinz’s “Common Sense Way.”

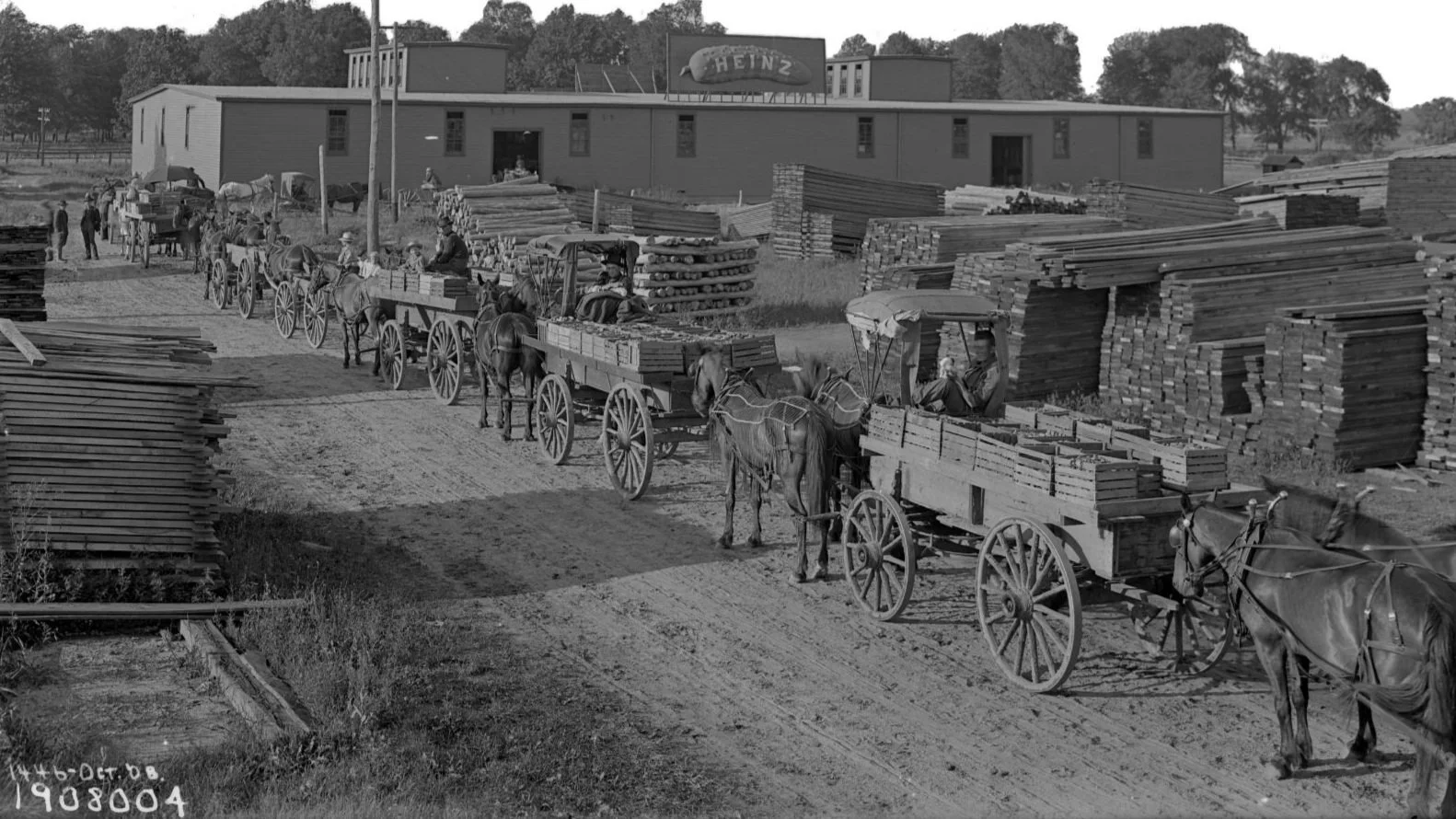

Cucumbers can become ripe in a matter of hours, thus, the ability of farmers to harvest and preserve the cucumber crops was paramount in maintaining the quality of the resulting pickle. Therefore, salting stations were strategically placed along railroads in communities near the cucumber fields, allowing farmers to get their crops to the salting stations as efficiently as possible. A company brochure states, “From the latter part of July until well into the month of September there is no more busy place than can be found at any Heinz receiving and salting station with its long lines of farmers’ teams and the bustle and activity attendant upon inspection, weighing and first rough sorting as each farmer comes up in turn to deliver his load.” From there, company-owned railroad cars full of cucumbers soaking in salty brine were whisked off to regional pickle factories where they were processed into pickle and relish varieties.[10]

In 1908 in Holland, Michigan, farmers with wagons full of boxes of cucumbers wait at the salting station.

“Line of horse-drawn wagons containing cucumbers,” H.J. Heinz Company, Photographs, 1864-1991, MSP 57, Library and Archives Division, Senator John Heinz History Center.

By 1904, Evart had its own Heinz salting station, a single-story frame building with a small one-and-a-half-story section, just outside the commercial corridor along a spur of the Flint and Pere Marquette Railroad.[11] Local newspapers like the Evart Review and Osceola County Herald published details on the travels of the Heinz Man through the area and the cucumber contracts each season. The cucumbers coming from Evart’s nearby fields likely made their way to one of Heinz’s Michigan factories in Grand Rapids, Holland, Holly, or Saginaw.

The 1904 Sanborn map of Evart shows the Heinz salting station on the east side of River Street, just north of Evart’s downtown. Notice that a spur of the Flint and Pere Marquette Railroad accesses the building.

Sanborn Map Company, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Evart, Osceola County, Michigan (New York: Sanborn Map Company, 1904), Library of Congress.

Instead of horses, these two girls use goats to pull their small wagon to the Heinz salting station in Evart.

David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photographs, University of Michigan

Michigan’s cucumber and pickling industry continued onward with seasonal advertisements for pickle contracts published in local newspapers throughout the later decades of the twentieth century, and articles published throughout the state about the importance of pickling cucumbers to local economies.[12] Michigan remains the country’s most prolific pickling cucumber producer and is purported to pack about one of every three pickles.[13] The world’s largest pickle factory? That’s in Michigan too. The Kraft-Heinz factory in Holland sprawls across 500,000 square feet as it produces vinegar, baked beans, and pickles. Michigan’s fertile soils, topography, and temperate climate provided the foundation from which the state’s agricultural prowess grew and have placed it at the center of the country’s pickling cucumber production since the turn of the twentieth century.[14]

[1] Mona Domosh, “Pickles and Purity: Discourses of Food, Empire and Work in Turn-of-the-Century USA,” Social & Cultural Geography 4, no. 1 (2003), 11; Nancy F. Koehn, “Henry Heinz and Brand Creation in the Late Nineteenth Century: Making Markets for Processed Food,” The Business History Review 73, no. 3 (Autumn, 1999), 350.

[2] Dana Terebelski and Nancy Ralph, “Pickle History Timeline,” New York Food Museum, accessed March 24, 2025, http://www.nyfoodmuseum.org/_ptime.htm; Koehn, “Henry Heinz,” 349-352.

[3] Koehn, “Henry Heinz,” 350.

[4] Koehn, “Henry Heinz,” 363-364.

[5] B. F. Bowen and Co., Bowen’s Michigan State Atlas (Indianapolis: B. F. Bowen and Co., 1916), 102.

[6] Domosh, “Pickles and Purity,” 11.

[7] H. J. Heinz Company, H. J. Heinz Company, Producers, Manufacturers and Distributors of Pure Food Products (Pittsburgh: H. J. Heinz Company, [1910]), HathiTrust.

[8] Koehn, “Henry Heinz.”

[9] “Men And Women Boys And Girls,” Osceola County Herald, April 15, 1920; “Getting Pickle Acreage,” The Holly Advertiser (Holly, MI), March 10, 1921; “County Seat Section,” Osceola County Herald, February 27, 1919; “East Lake County,” Osceola County Herald, December 14, 1922; “Seed Free,” Osceola County Herald, March 13, 1924.

[10] Nina Misuraca Ignaczak, “Why Michigan is a Pickle Powerhouse,” interview by Stateside Staff, Michigan Public Radio, August 15, 2019, https://www.michiganpublic.org/politics-government/2019-04-15/stateside-using-algorithms-to-set-bail-michigan-is-a-pickle-powerhouse-invasive-lanternfly-risk; Koehn, “Henry Heinz,” 390.

[11] Sanborn Map Company, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Evart, Osceola County, Michigan (New York: Sanborn Map Company, 1904, 1910, 1920, 1942), Library of Congress.

[12] Jeff Alexander, “Hold The Pickle? Not These Guys,” Muskegon Chronicle, March 16, 1992; “In A Pickle,” Saginaw News, April 23, 2009; Earle Berry, “West Michigan Is Pickle Country,” Muskegon Chronicle, August 20, 1975; “Pickle Contracts,” Pinconning Journal, April 2, 1975; Nina Misuraca Ignaczak, “Why Michigan Is The Center Of The ‘Pickleverse’,” Pinconning Journal, August 14, 2019, https://www.pinconningjournal.com/lifestyles/why-michigan-center-%E2%80%98pickleverse%E2%80%99; “Notice – Get Your Pickle Contract,” Vassar Pioneer Times, April 29, 1965.

[13] “Michigan’s In A Pickle And Loving Every Bite Of It,” Chicago Tribune, August 19, 2021, https://www.chicagotribune.com/1995/05/22/michigans-in-a-pickle-and-loving-every-bite-of-it/.

[14] Nina Misuraca Ignaczak, “Why Michigan Is The Center Of The ‘Pickleverse’,” Pinconning Journal, August 14, 2019, https://www.pinconningjournal.com/lifestyles/why-michigan-center-%E2%80%98pickleverse%E2%80%99.